My old neighborhood, Noe Valley, is an expensive area of San Francisco (I know, redundant) filled mostly with affluent young couples starting families, and old codgers that got into the housing market years ago when it was a bargain. The neighborhood’s local paper is called the “Noe Valley Voice,” a monthly free publication filled with charming local news and letters to the editor which are often lunatic rants by residents desperate to find something to complain about.

Whenever a new issue of the Noe Valley Voice would come out, my wife and I would eagerly turn to the “Letters to the Editor” and read them aloud in our most annoyed voice. Noe Valley is gorgeous and very safe. What’s to complain about living in one of the most ideal neighborhoods of San Francisco? Every month we find yet another neighbor who has found a way, whether it’s complaining about the ugliness of a newly painted crosswalk or demanding the community force a neighborhood ordnance that requires Noe Valley residents take down their Christmas decorations by January 1st.

Anyone who has ever worked in media is very familiar with these readers. We count on them to call and send in letters so we have comedic fodder for our editorial meetings. And to show that we truly care and appreciate their ungrounded complaining, we let one of their letters get published during a slow news day. Other than that, these readers have never had an influence on any editorial or business decision. In fact, to let them give voice to any critical decision would be business suicide.

Hold that thought for a moment as we go into a discussion about native advertising.

Native advertising could be a publication’s savior and its demise

Guess who just blew into advertising-ville? Native advertising, it’s a form of sponsored content that lives in line with the rest of the publication’s content, not banished to the side in advertising world where nobody looks or clicks. In an effort to generate new found revenue and save their publication’s existence, major media outlets, such as the NYTimes, Forbes, TIME, and Washington Post, have begun offering native advertising. With all the excitement around content marketing, native advertising could potentially be a huge windfall for the media industry. While the editorial staff wants to keep its job by bringing more money in, they will do whatever it takes to make sure native ads are never mistaken for actual editorial content even if it means imposing so many restriction that their sales staff can’t possibly sell a native ad.

While the American Society of Magazine Editors (ASME) is trying to create some standards for native advertising, every publication is handling it differently. In every case I’ve seen of a native ad, it’s clearly indicated that the content was produced by some company and in some cases it also says the content is “sponsored.” I’m sure readers have seen differently, will debate this assertion, or believe there’s tons of pay to play going on that we don’t know about. That may be true, but let’s assume that all those who choose to participate in native advertising choose to simply indicate who or what is responsible for the content’s publication.

While the American Society of Magazine Editors (ASME) is trying to create some standards for native advertising, every publication is handling it differently. In every case I’ve seen of a native ad, it’s clearly indicated that the content was produced by some company and in some cases it also says the content is “sponsored.” I’m sure readers have seen differently, will debate this assertion, or believe there’s tons of pay to play going on that we don’t know about. That may be true, but let’s assume that all those who choose to participate in native advertising choose to simply indicate who or what is responsible for the content’s publication.

NYTimes’ native ads are DOA

Some publications are so concerned that readers will confuse sponsored content with the publication’s editorial content that they demand more warnings, more labels, and more segmentation of native ads. For example, the NYTimes has TWELVE separate indicators and warnings to let you know that this content is coming from a paid vendor. These warnings include multiple mentions of the advertiser, a separate subdomain (paidpost.nytimes.com), a TITLE tag that begins with the words “Paid Post,” plus the article is printed in a sans serif font (NYTimes articles are published in a serif font), and have a layout and coloring that’s different from the rest of NYTimes’ content (see DELL example). The only thing that lets you know you’re still on the NYTimes site is the banner of links at the top. Yeah, I get it NYTimes, this is not an article you wrote, nor something anyone wants to read.

I wonder if these warnings are affecting performance in any way.

I wonder if these warnings are affecting performance in any way.

A recent report on TIME from Tony Haile, CEO of Chartbeat, indicates that native ads, the supposed banner ad savior, are actually not doing nearly as well as the rest of the editorial-based content. His company’s data, which measures readership of 4,000 publishers and brands, noted the following:

On a typical article two-thirds of people exhibit more than 15 seconds of engagement, on native ad content that plummets to around one-third. You see the same story when looking at page-scrolling behavior. On the native ad content we analyzed, only 24% of visitors scrolled down the page at all, compared with 71% for normal content.

Why are these native ads performing so poorly? Is it because the editorial of all these sites is so consistently more awesome? Or is it because publishers like the NYTimes are so frightful of native ad/editorial confusion that they slap twelve “this isn’t our content so you’ll probably not like it” warnings?

Native ads never had a chance

Not all publishers are treating native advertising like the NYTimes. There are some that simply indicate that the article is brought to you from a brand and they leave it at that because that’s all an intelligent reader needs – one indicator to let you know who’s responsible for a specific piece of content. It’s the same reason every author only gets one byline and not twelve. An intelligent reader knows exactly where to look if they want to know who is responsible for the article.

But excessive native ad warnings, à la NYTimes, aren’t designed for the intelligent reader. They’re designed for a publication’s absolutely dumbest readers. The same morons who write idiotic letters to the editor that get laughed at during editorial meetings. Those same idiots are now dictating a publication’s business decisions.

Having been in media for many years I know that no matter how many warnings and directions we would give to our audience, there was always one idiot who never gets it. They’ll send in a letter and complain.

Instead of bringing that letter to the editorial meeting and laughing at him like you should, editorial staff, fearful of continued native ad/editorial confusion, will use that one letter as an argument to demand more warnings on native ads. It’s an understandable response. A publication’s editorial is the reason for its existence. But if you’ve been treating these idiots like buffoons before the existence of native ads, then why should you stop? They didn’t all of a sudden get any smarter. They’re still the same wing-nuts you laughed at before.

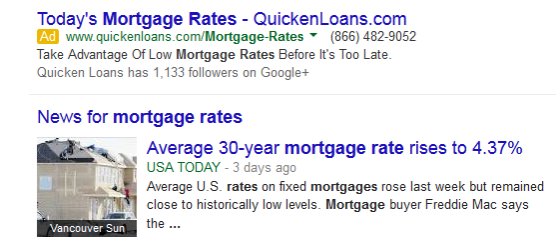

Google doesn’t care

Have you noticed over time that the visual indicators that separate Google’s sponsored search results from actual search results are barely visible? They used to be color coded differently, had clear labels, and were physically separated from the real search results. Now, one can barely tell the difference. Google’s algorithm for its natural search results are the reason for its existence. Their search results are its editorial brand. But over time they’ve learned that the excessive warnings weren’t necessary anymore. That people understood where the sponsored and real results lived.

This natural evolution may eventually happen for native advertising. There may come a standard way all publications present native ads so that it’s clear that the ad is not true editorial, but at the same time part of the overall feel and look of the publication.

If a native ad or sponsored content is clearly labeled as brought to you by some company, and someone still writes in thinking that it’s editorial for your newspaper, then publications must make the same conclusion they’ve always made. These people are idiots! Either ignore them or bring their responses into an editorial meeting for a good laugh. Don’t let their behavior be used as evidence to construct more walls against native ads.

Creative Commons photo courtesy of splorp.